<< Back

Navigating a Pandemic Without Sound: Getting Vaccines to the Deaf

May 24, 2021

We tend to take a lot of things for granted. When the pandemic first hit last year, little luxuries like going to the store, to the movies, just seeing friends and family all went away. The level of frustration was palpable.

But what if you couldn’t hear?

“I went to the grocery store, with masks, staying six feet apart. And the cashier kept telling me to move,” said Luisa Soboleski, President of the Connecticut Association for the Deaf. “The cashier is speaking, but I can’t hear her, I can’t read her lips, but she just kept talking. It looked like she was screaming louder and louder.”

You can’t hear, you can’t read lips, and the people you are trying to communicate with don’t know sign language.

“My biggest concern is that there are deaf people who can’t read, they can’t read lips,” said Soboleski. “They are out there. For deaf people who can’t read lips, what’s their backup?”

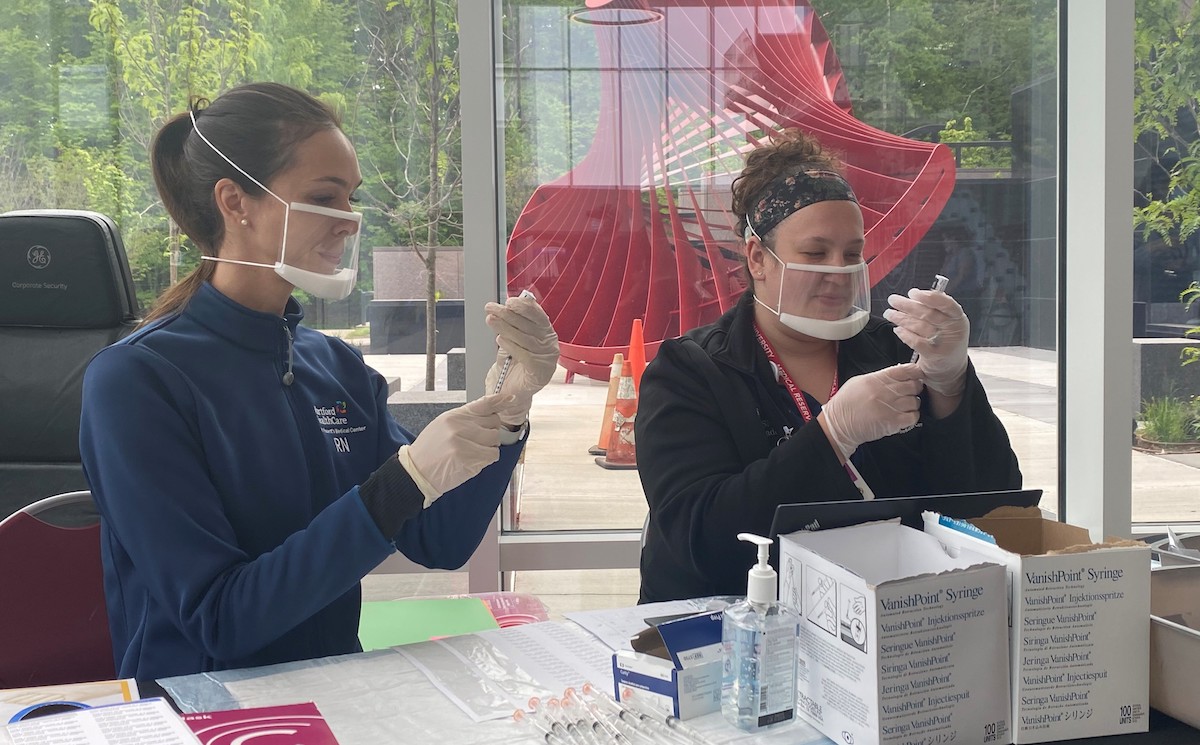

This need during COVID-19 has led to a partnership between Hartford HealthCare and the American School for the Deaf in West Hartford that has created special vaccination clinics across the state, including sites at Foxwoods Casino, the Connecticut Convention Center in Hartford and the Oakdale Theatre in Wallingford.. The goal is to inoculate as many deaf students — and members of the deaf community — against the coronavirus.

“As a healthcare organization, it is so important that we make it as easy and convenient as possible for people to get vaccinated,?” said Backus Hospital Outpatient Services Practice Director Darleen Caisse, who helped staff the Foxwoods clinic for the deaf. “We are so close to putting this pandemic behind us, but we still have work to do. Community outreach like this, including reaching those who are deaf, is what will help us achieve herd immunity and put COVID in the rearview mirror. I am proud to work for an organization that is dedicated to helping people in the community – all people in the community – live healthier lives.”

During the early stages of COVID-19 testing, many healthcare centers did not have interpreters for the deaf. Once the vaccine rollout began, the lack of sign language translations once again became an issue. Connecticut Association for the Deaf Board Member Paul Ditimi said that even when clinics know a member of the deaf community is coming, proper accommodations aren’t always made.

“I was at the hospital for the vaccine,” he said. “The first time I was there, they got an in-person interpreter for me. The next time, there was no interpreter. They tried to take out the video interpreting system, and they are trying to set it up, but it’s not working. They said they would take care of it. I was like, ‘So you want me to sit here for and wait two hours for an interpreter to show up? I can’t do that. That’s ridiculous.’”

Ditimi called one of his friends, a certified translator, and set up a FaceTime session between the health officials and the interpreter.

“Being deaf, I was able to manage it, but what about others?” said Ditimi. “How will they be able to handle it? It’s not about my experience, it’s about the deaf community. I don’t want them to have to go through something like that. There are a lot of people who may not be able to communicate as well as me, or be able to put something together like I did. I need those people to get those services.”

Soboleski and her organization attended the clinic at Sacred Heart University in Fairfield, volunteering to serve as interpreters for anyone in their community who needed help. It’s a partnership Soboleski says is a long time coming.

“This should have been done months ago, but that’s OK,” she said. “If we need booster shots in the future, we know that we can set these up in a much more efficient way and get the word out. So things have improved.”

Improved, but not totally fixed. Like many groups, vaccine hesitancy does exist among those in the deaf community. Creating special clinics with interpreters is a large step in the right direction. But the challenge remains of actually letting people know the clinics exist, and convincing them to get the shot.

“Many deaf people are scared of the vaccine because of the stories they hear,” said Soboleski. “Obviously, you can try to convince them, but you can’t force them. We are now doing video blogs for deaf people. We do them in sign, and I talk about my experience. We need to be in contact with the deaf community because many people don’t have cable to connect to video phones. Some people can’t afford smartphones. We have to find the best way to get this information across the community.”